A businessman living in Pangyo New Town typically spends over an hour crawling through Seoul traffic to reach his office in Gwanghwamun. By UAM, that same 25-kilometer journey takes just 15 minutes. He books his seat through the integrated Seoul mobility app, walks to the nearby vertiport, goes through streamlined security screening, and boards a five-seat eVTOL aircraft.

Within minutes, he's soaring above the Han River, watching the morning traffic jams shrink below. As his aircraft follows the designated river corridor, he glimpses construction crews working on Seoul's new floating hotel and office complexes, part of the city's Great Han River Project that's creating an integrated three-dimensional transportation network connecting land, water, and air. By 2030, those same floating facilities will serve as waypoints and passenger amenities for the UAM routes he's flying today.

The Republic of Korea’s Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport unveiled sweeping plans in August 2025 that will establish the foundation for a robust low-altitude economy operating below 1,000 meters. But this isn’t another government announcement full of empty promises. South Korea has already invested billions in infrastructure, tested the technology, and established the regulatory framework necessary to make flying cars a reality for millions of people.

The K-UAM Grand Challenge: Proving It Works

Joby eVTOL Fly in Korea’s K-UAM Grand Challenge

Joby eVTOL Fly in Korea’s K-UAM Grand Challenge

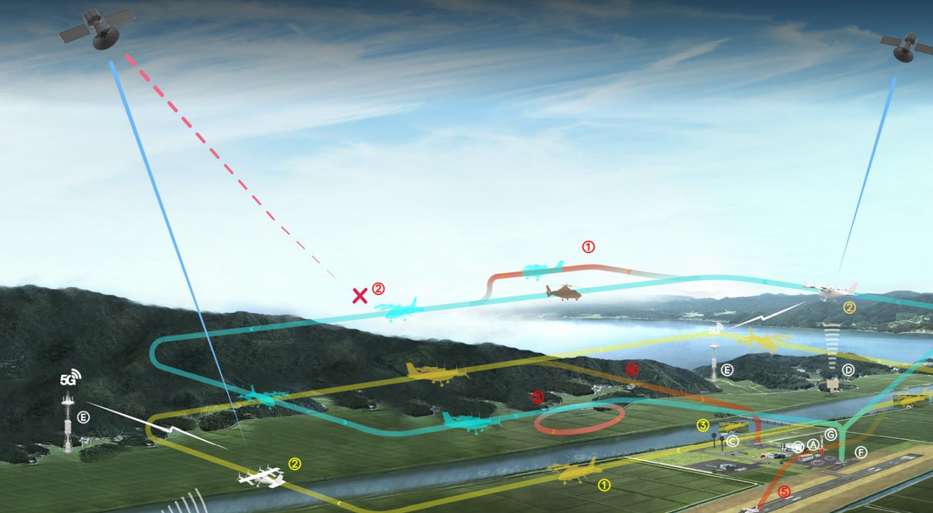

At the heart of South Korea’s approach lies the K-UAM Grand Challenge, a massive demonstration program that brings together the country’s biggest companies and international partners to test every piece of the urban air mobility puzzle.

The program has already achieved what most nations haven’t even attempted. In December 2024, Joby Aviation became the first company to complete flights as part of the Grand Challenge, demonstrating various flight profiles over a week of testing. Korean Air followed up with its own comprehensive demonstration that validated an entire urban air mobility system using 5G networks to link aircraft with ground-based traffic management systems.

These aren’t just publicity stunts. The Grand Challenge requires companies to prove their technology can handle Korean weather conditions, urban environments, and the specific challenges of flying over densely populated areas. Seven consortiums are currently competing in this real-world testing program that will determine which companies get to operate commercial services when they launch.

Building the Infrastructure That Makes It Possible

South Korea is building the physical infrastructure that will support thousands of daily flights. The country is updating building codes to require new “smart plus” buildings to include vertiport facilities on their rooftops. Major hospitals and government buildings are already being designed with landing pads for emergency transport and commuting.

Seoul plans to have four operational vertiports by 2030 at key locations, including Yeouido, Gimpo International Airport, Suseo, and Jamsil. But the most impressive infrastructure project is happening in Goyang, a Seoul suburb that’s constructing Korea’s first commercial vertiport on an 18,000 square meter site near the KINTEX convention center. When completed in June 2026, passengers will be able to travel from KINTEX to Gimpo Airport in approximately 15 minutes.

The government has also approved vertiports at maritime port facilities, recognizing that the coastal geography of South Korea makes these locations ideal connection points between cities and airports.

Seoul takes this integration philosophy even further with its Han River developments. The city is constructing floating facilities—including a hotel, office complex, and food zones—specifically positioned along planned UAM corridors. These aren't separate projects but coordinated infrastructure that creates passenger amenities and intermediate stops for air mobility routes. The floating hotel near Yeouido, completing in 2028, exemplifies this approach: guests can arrive by UAM, enjoy river views, then continue their journey by air, water, or ground transportation.

This level of integrated planning shows how seriously the country takes the practical challenges of operating urban air mobility at scale.

The Han River Corridor: Where Three Worlds Meet

A projected image of the “floating food zone” on the Han River, scheduled to begin construction in 2026 (Seoul Metropolitan Government)

A projected image of the “floating food zone” on the Han River, scheduled to begin construction in 2026 (Seoul Metropolitan Government)

Seoul's Han River isn't just a flight path—it's becoming the world's first integrated three-dimensional transportation corridor. While eVTOL aircraft soar overhead at 1,500 feet, floating hotels, offices, and restaurants are taking shape on the water below, creating a unique ecosystem where air, water, and land transportation converge.

The city's Great Han River Project explicitly integrates UAM services with floating infrastructure. By 2028, passengers arriving at the floating hotel near Seogang Bridge can catch connecting UAM flights to Gimpo Airport. The 18-kilometer route from Gimpo to Yeouido follows the river corridor, offering passengers aerial views of the floating facilities that serve as both destinations and visual landmarks for navigation.

This isn't accidental urban planning. Seoul designed the floating developments to complement rather than compete with aerial transportation. The floating office complex in Ichon-dong includes marina facilities that could easily accommodate emergency landing areas, while the planned floating food zone offers passengers a unique dining destination accessible only by water taxi or air taxi.

The 5G Network That Guides Every Flight

South Korea’s secret weapon in the low-altitude economy isn’t just the aircraft or the landing pads. It’s the invisible digital infrastructure that will make thousands of simultaneous flights possible without collisions or chaos.

The country is building a 5G-based airspace network that serves as the nervous system for urban air mobility operations. This network provides communication, navigation, and surveillance services that help aircraft locate their position, avoid collisions, and reach destinations safely. Unlike traditional aviation that relies on ground-based radar, South Korea’s system uses mobile telecommunications to create a three-dimensional traffic management system.

Korea Telecom has already developed and tested specialized antennas that work at altitudes up to 600 meters and cover widths of 100 meters. The company’s tests confirmed that the system can handle cell handovers and signal interference at the speeds and altitudes where urban air mobility operates. This 5G aviation network will be completed in its first phase by the end of 2025.

During Korean Air’s demonstration, over 100 million pieces of real-time data flowed through the system - flight plans, aircraft locations, weather alerts, and safety warnings. When an aircraft approaches Gimpo Airport, the 5G network automatically coordinates with air traffic control, guides the pilot to the designated landing pad, and updates passengers’ connecting ground transportation about the arrival time.

Companies Betting Big on Korean Skies

The Korean government’s commitment has attracted major international players and sparked serious investment from domestic companies. Korean Air is building a 1.2 trillion won Urban Air Mobility hub in Bucheon that will employ more than 1,000 people when it opens in 2030. The facility will focus on next-generation software and artificial intelligence for unmanned aerial vehicles.

Major Korean consortiums are forming partnerships with leading global manufacturers. The K-UAM Dream Team includes SK Telecom, Hanwha Systems, TMAP, and Korea Airports Corporation, working with Joby Aviation. Another consortium called UAM Future Team brings together GS Engineering & Construction, LG U+, Kakao Mobility, and Vertical Aerospace.

But South Korea isn’t just importing foreign technology, it’s developing its own. Hyundai Motor Group’s Advanced Air Mobility division, Supernal, represents Korea’s homegrown answer to the global eVTOL race. The company’s S-A2 aircraft puts Korean automotive engineering directly into the sky.

Hyundai Supernal S A2 in flight

Hyundai Supernal S A2 in flight

The S-A2 isn’t just another concept vehicle. This five-seat aircraft (one pilot, four passengers) targets the exact routes that will matter most to Korean commuters: 25 to 40-mile trips at 120 miles per hour, cruising quietly at 1,500 feet. With eight tilting rotors and a distinctive V-tail design, the aircraft produces just 45 decibels of noise during horizontal cruise, quieter than most ground traffic.

Supernal brings something unique to Korea’s urban air mobility push: the manufacturing expertise that built Hyundai into one of the world’s largest automakers. The company plans to leverage Hyundai’s mass production capabilities to keep costs down while meeting commercial aviation safety standards. This manufacturing approach could give Korean-made aircraft a significant cost advantage over boutique aerospace manufacturers.

The company has already proven its technology works in Korean conditions. During the K-UAM Grand Challenge demonstrations at Goheung Aviation Test Center, Hyundai Motor tested its comprehensive mobility-as-a-service platform while collecting crucial data on weather and wind conditions that affect eVTOL operations. Korean Air validated its traffic management systems by linking them to Supernal’s aircraft through 5G networks, proving the entire ecosystem can work together.

Supernal’s timeline aligns perfectly with Korea’s commercialization plans. The company targets market entry in 2028, positioned to serve the commercial routes that Seoul plans to launch by 2030. This means Korean passengers may soon experience urban air mobility in aircraft designed and built by Korean companies, not just imports flying in Korean skies.

Even foreign companies are making significant commitments. Sora Aviation secured a pre-order for 20 of its 30-seat eVTOL aircraft from Korean helicopter operator Moviation, with plans to operate routes between Jamsil Heliport and Incheon Airport. Eve Air Mobility signed agreements with UI Helicopter to develop the technical and operational requirements for advanced air mobility in South Korea.

The Timeline That Sets Korea Apart

What makes South Korea’s low-altitude economy plans so remarkable isn’t just their scope, it’s the aggressive timeline. The country will begin demonstration flights in the first half of 2025, with Seoul starting test operations over Yeouido and the Hangang River. That’s not a distant goal or a hopeful projection. It’s happening in the next few months.

The Han River corridor serves as both a protected flight path away from restricted military airspace and a showcase for how urban air mobility integrates with waterfront development.

These initial demonstrations will connect the Korea International Exhibition Center to Gimpo International Airport and Yeouido Park, giving passengers their first taste of what urban air mobility feels like in real Korean skies.

The Han River corridor isn't just a flight path, it's becoming Seoul's showcase for integrated mobility innovation. The city's Great Han River Project deliberately aligns floating hotel construction (completing in 2028) with UAM commercialization, creating what officials call 'three-dimensional transportation.' Passengers will soon book combined experiences: flying over the river at sunset, then landing at floating facilities for dining or meetings, all coordinated through Seoul's integrated mobility app.

But the demonstrations are just the beginning. Seoul plans to launch commercial urban air mobility services by 2030, then expand into a complete network covering the metropolitan area by 2040.

This accelerated timeline is possible because South Korea has spent years building the regulatory framework to support it. The country enacted a Special Act on the Promotion of Urban Air Mobility Commercialization that provides legal grounds for administrative and financial assistance to the industry. The law establishes regulatory exceptions and business support specifically designed to turn test flights into paying passengers as quickly as possible.

The phased approach reflects Korea’s methodical strategy. Test the technology with demonstrations in 2025. Prove the business model with commercial routes by 2030. Scale up to full network coverage by 2040. Each phase builds on the last, creating a pathway from science experiment to everyday transportation that passengers can actually rely on.

Breaking Through Korea’s Sky Barriers

South Korea’s push into urban air mobility faces a challenge that makes other countries’ regulatory hurdles look simple: most of the nation’s metropolitan areas are currently de facto no-fly zones because of safety and security reasons. The very cities where urban air mobility would be most valuable are the same places where aircraft have been strictly prohibited from operating.

Seoul presents the starkest example of this restriction. The capital sits under multiple layers of airspace controls that effectively ban most aviation activity. Central and northern Seoul fall under special no-fly zones designated “P-73A” and “P-73B” that cover the area around the former Blue House presidential residence and government complexes. Beyond that, a broader restricted zone, “R-75,” blankets most of metropolitan Seoul, requiring special military authorization for any aircraft operations.

The restrictions extend far beyond government buildings. Significant portions of western Seoul and surrounding areas are off-limits due to control zones around Incheon International Airport and Gimpo Airport, each creating roughly 5.5-kilometer radius exclusion zones. Add in restrictions around military installations, critical infrastructure like nuclear power plants, and populated areas where flying over crowds is prohibited, and the available airspace shrinks dramatically.

These aren’t arbitrary bureaucratic obstacles. South Korea’s unique security environment, including its proximity to North Korea and the ongoing armistice conditions, has shaped decades of restrictive airspace policies. The Korean Demilitarized Zone creates additional no-fly buffers extending up to 40 kilometers from the Military Demarcation Line for fixed-wing aircraft and 15 kilometers for unmanned aerial vehicles. Recent incidents, including North Korean drone intrusions into Seoul’s airspace in 2023, have only reinforced the military’s vigilant approach to unauthorized aircraft.

For urban air mobility to work, South Korea must solve what no other country has attempted at this scale: safely opening heavily restricted urban airspace while maintaining national security. The government recognizes this challenge directly. Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport officials have launched discussions with the defense ministry and Seoul city to lift prohibited airspace areas specifically for UAM operations. The most logical routes for urban air mobility services run from Gimpo International Airport or Incheon International Airport along the Han River to Seoul downtown, cutting directly through some of the most restricted airspace in the country.

The breakthrough comes through South Korea’s comprehensive regulatory approach. The Special Act on the Promotion of Urban Air Mobility Commercialization doesn’t just create business incentives; it establishes regulatory exceptions that allow UAM aircraft to operate in areas where other aviation is banned. The government is creating a new category of aviation that can function within the existing security framework rather than trying to dismantle decades of airspace restrictions.

This regulatory innovation explains why South Korea’s timeline is so aggressive compared to other countries. While nations with open airspace debate how to integrate new aircraft types, South Korea is simultaneously solving the much more complicated problem of creating viable flight corridors in heavily restricted urban environments. The country’s methodical approach through the K-UAM Grand Challenge allows officials to test these airspace changes gradually, proving that urban air mobility can operate safely without compromising national security.

The success or failure of South Korea’s approach will determine whether urban air mobility can work in other security-conscious urban environments worldwide. If Korean officials can make flying taxis work in Seoul’s restricted airspace, they’ll have solved one of the most complex aviation challenges facing cities around the globe.

The Broader Economic Vision

South Korea’s low-altitude economy extends far beyond just moving people around cities. The country sees urban air mobility as part of a broader ecosystem that includes drone deliveries, agricultural applications, emergency services, and tourism operations.

The government has designated reserved airspace for low-altitude use, with streamlined approval processes that allow flights for logistics, tourism, and emergency transport with just one hour’s advance notice. This regulatory flexibility creates opportunities for companies to develop new business models that wouldn’t be possible in more restrictive environments.

The country’s investment in this industry is substantial but strategic. The Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport plans to invest 100.7 billion won in developing core technologies for safe urban air mobility operations. The Korea Aerospace Administration has committed 806.4 billion won across 44 aerospace research and development projects for 2025.

Tourism Takes Flight Over the Han River

Seoul's approach to UAM extends beyond commuting into experiential tourism that showcases the technology's potential. The city's Great Han River Project explicitly integrates UAM flight tours with floating infrastructure development, creating what Mayor Oh Se-hoon calls "Korea's blueprint for the future."

Starting in 2025, tourists will experience "UAM flight tour routes over the Han River" as an official government service. These aren't just sightseeing flights—they demonstrate how urban air mobility connects with other transportation modes. Passengers might fly from Gimpo Airport, enjoy aerial views of the river and city skyline, then land at Yeouido near the under-construction floating hotel complex.

The integrated approach transforms the Han River from Seoul's recreational heart into a living laboratory for urban mobility. By 2030, when floating hotels and office complexes open alongside commercial UAM routes, visitors will experience a fully integrated system where air, land, and water transportation work together seamlessly. This holistic approach positions Seoul as a global model for cities seeking to integrate advanced air mobility with existing urban infrastructure.

The Competitive Advantage of Moving Fast

While other countries debate the feasibility of flying taxis, South Korea is building the infrastructure, testing the technology, and training the personnel needed to operate them safely at scale. This first-mover advantage could position the country as a global hub for low-altitude economy technologies and services.

Major Korean telecommunications companies are developing the traffic management systems that will be needed worldwide as other countries eventually follow South Korea’s lead. Korean construction companies are gaining expertise in vertiport design and construction that will be valuable as global demand grows.

The country’s approach combines strong government support with serious private investment, creating an environment where new technologies can be tested and commercialized quickly. This combination of policy support, infrastructure investment, and regulatory flexibility gives South Korea advantages that are difficult to replicate in countries with more fragmented approaches to innovation.

South Korea isn’t just talking about the future of transportation, it’s building it. The low-altitude economy may have started as a science fiction concept, but in Korean skies, it’s about to become an everyday reality.